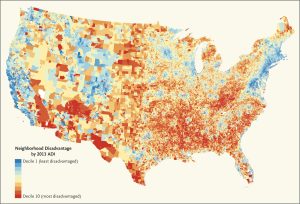

For years, Dr. Amy Kind has been keenly aware that the neighborhoods in which her patients live often hinder their recovery. She described, for example, how worries over neighborhood safety deter home health care staff from visiting some of her low-income patients to check on their recovery. In one case, that lack of follow-up care meant a 78-year-old patient with mild dementia forgot to take his antibiotics to treat his pneumonia, and was readmitted three days after leaving the hospital.

For years, Dr. Amy Kind has been keenly aware that the neighborhoods in which her patients live often hinder their recovery. She described, for example, how worries over neighborhood safety deter home health care staff from visiting some of her low-income patients to check on their recovery. In one case, that lack of follow-up care meant a 78-year-old patient with mild dementia forgot to take his antibiotics to treat his pneumonia, and was readmitted three days after leaving the hospital.

Kind, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, also described the futility of, say, diabetes education for patients who live in substandard housing that lacks adequate refrigeration in which to store insulin. Or how some people are too embarrassed to tell their doctors that they often can’t afford to heat their homes….

To read the rest of the column, visit its original posting site at the Center for Health Journalism.

When Jennifer Bui, a resident of the low-income San Diego neighborhood of City Heights, turned 18, she started concentrating on her financial future.

When Jennifer Bui, a resident of the low-income San Diego neighborhood of City Heights, turned 18, she started concentrating on her financial future.